April 2020

Beautiful Place by Amanthi Harris is a beautiful book that stands out because of its exquisite narrative. The author has painted a beautiful canvas with characters both dark and light that create a perfect symphony and draw you right away into the world of Padma and Gerhardt tucked away on the exquisite southern coast of Sri Lanka… The story makes us question the concept of family and home. Is family constituted by just blood relationships or does it transcend to something higher and nobler ? Blood ties alone cannot translate to a family. Relationships that allows you to grow, to spread your wings with the safety net of love, which allows to to trust without having to second guess, to communicate openly and honestly are the ones that become your family in the long run. Blood relationships do exert their pull but if there is the shadow of distrust, greed and ulterior motive lurking somewhere, then these relationships do not stand the test of time. Is home just a structure of brick and mortar or a place where you are accepted unquestioningly with open arms? The characters in this story eventually realize the true meaning of home and family and in the process find themselves.

The story is set against the backdrop of the beautiful tropical island of Sri Lanka where nature reigns in its unadulterated, raw and pristine glory. But as is the case with life, where there is extreme beauty, ugliness too finds a way to creep in. The ugly and dark face of greed and corruption casts a dark shadow on the protagonists and threatens to uproot their safe haven. … Somewhere along the narrative, the concept of home assumes a much broader meaning. Home is an abode of beauty, of peace, of serenity – in short, a beautiful place…. Depending on the context, it can be a brick and mortar building, a locality, a city or a country. It can also be an abode of happiness ensconced in the deep recess of one’s heart…

Full review: https://bongbooksandcoffee.com/2020/04/22/beautiful-place-amanthi-harris

The Hindu Business Line 13 March 2020

With an idyllic beach resort as the centrepiece, Amanthi Harris’s new novel is about the pursuit of happiness in a country as beautiful — and messy — as Sri Lanka

Where is home? Does a place of birth exert an unknowable pull on us? Can home be found far away, among people removed from our life? Amanthi Harris’s Beautiful Place, set in modern-day Sri Lanka, delves into these thoughts and more.

Harris, who was born in Sri Lanka and brought up in London, won the Gatehouse Press New Fictions Prize in 2016 for the novella Lantern Evening.

In Beautiful Place, she depicts a Sri Lanka that is indeed beautiful. In fact, the physical beauty of the land is almost a character in its own right — the lushness of its greenery, the azure of its waters, the darkness of the nights, the brilliance of the flowers… all inhabit the book and speak to the reader. Yet, lurking among them are human lives — messy, complicated, and often cruel.

Padma is a young and enthusiastic owner of a guest house near a beach in southern Sri Lanka. The house was designed and built by Gerhadt, an Austrian expat and Padma’s adoptive father. When Padma was still a child, her biological father, Sunny, had tried to sell her to Gerhadt. She was adopted, instead, and her life moved away from the abuse and poverty of the circumstances of her birth. She grew into a woman surrounded by love. But can upbringing erase the pain of early childhood? Harris returns to this question again and again in the book.

While Padma seems to have everything she could need, there is an emptiness within her that she can’t shake off, and which seems to take over her life once she returns from Colombo to start the guest house business.

The novel fills up with characters as guests arrive at the villa. Their stories unfold and we watch as these gradually enmesh with Padma’s life. The people bring in the larger world with them, so too their own complicated histories and heartaches. Through them the stories of a Sri Lanka outside the walls of the villa seep in. But outside the boundaries of the villa also lies the world of Sunny. A constant and dangerous presence, he claims to still have rights over his child Padma, threatening to bring back chaos in his wake.

Harris juxtaposes these two worlds — life at the villa with its routine of hospitality and friendships, and the looming outside world with its complications of politics, economics, race and cultural barriers.

The villa almost seems a place of refuge — one where people can move on from the sadness that gripped them elsewhere and find solace in its simple food, the beauty of its garden, the friendly presence of Gustav the dog.

Yet it’s clear that the world cannot be wished away. While all of this would have remained fairly innocuous, it is with the growing discontent over a book that the action seems to explode.

Jarryd, an expat and a yoga practitioner, has written a history of the country that lays bare the fissures in its society. Sections from Jarryd’s book appear within the novel, giving a perspective on Sri Lankan history and culture. But Jarryd’s writing also ruffles the feathers of powerful politicians and they start circling in, bringing with them violence and torture.

Then there is the village where Padma’s biological family lives — one with whom she has nothing in common any more and, yet, with whom she has a visceral connection. It exerts an irresistible pull on her, taking her there against the cautious judgement of Gerhadt.

Harris carefully builds a world, piling lives together, weaving in threads and networks. She shows how the past lives in the present — whether in an individual’s life, or in the life of a nation. That nothing ever really goes away unless the people involved are ready to let it recede. Where she succeeds is in creating the multiple characters and the setting. The people are alive in the pages, grappling with their faults and virtues. Padma is an interesting person — brave, generous, yet confused. As are Gerhadt and Jarryd.

For full review: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/blink/read/retreat-from-chaos-in-sri-lanka/article31058559.ece#

Sussex Life Magazine – February 2020

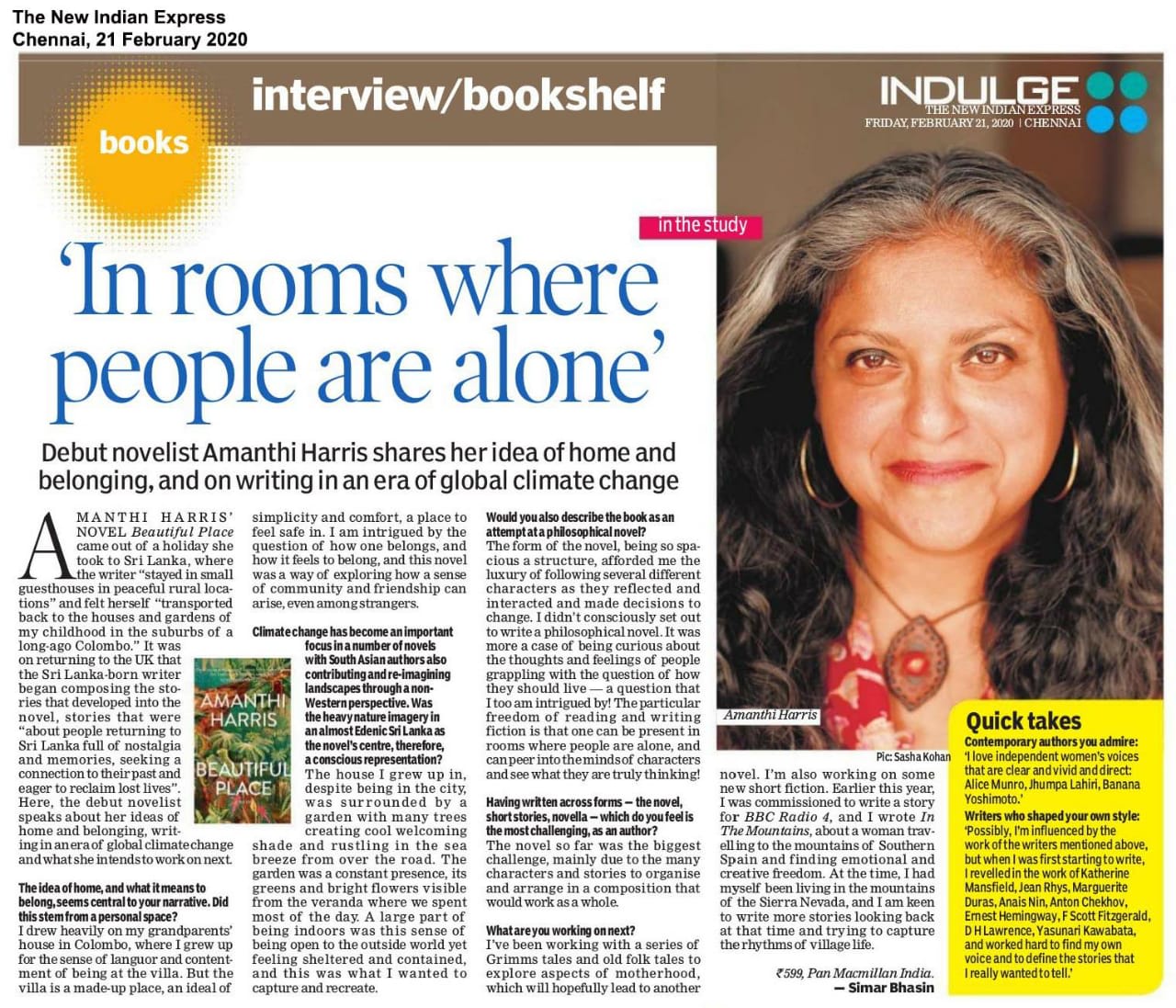

The New Indian Express – February 2020

By Simar Bhasin The New Indian Express

NEW DELHI: Amanthi Harris’ novel ‘Beautiful Place’ came out of a holiday she took to Sri Lanka, where the writer “stayed in small guesthouses in peaceful rural locations” and felt herself “transported back to the houses and gardens of my childhood in the suburbs of a long-ago Colombo.” It was on returning to the UK that the Sri Lanka-born writer began composing the stories that developed into the novel, stories that were “about people returning to Sri Lanka full of nostalgia and memories, seeking a connection to their past and eager to reclaim lost lives”. Here, the debut novelist speaks about her ideas of home and belonging, writing in an era of global climate change and what she intends to work on next.

The idea of home, and what it means to belong, seems central to your narrative. Did this stem from a personal space?

I drew heavily on my grandparents’ house in Colombo, where I grew up for the sense of languor and contentment of being at the villa. But the villa is a made-up place, an ideal of simplicity and comfort, a place to feel safe in. I am intrigued by the question of how one belongs, and how it feels to belong, and this novel was a way of exploring how a sense of community and friendship can arise, even among strangers.

Climate change has become an important focus in a number of novels with South Asian authors also contributing and re-imagining landscapes through a non-Western perspective. Was the heavy nature imagery in an almost Edenic Sri Lanka as the novel’s centre, therefore, a conscious representation?

The house I grew up in, despite being in the city, was surrounded by a garden with many trees creating cool welcoming shade and rustling in the sea breeze from over the road. The garden was a constant presence, its greens and bright flowers visible from the veranda where we spent most of the day. A large part of being indoors was this sense of being open to the outside world, yet feeling sheltered and contained, and this was what I wanted to capture.

Would you also describe the book as an attempt at a philosophical novel?

The form of the novel, being so spacious a structure, afforded me the luxury of following several different characters as they reflected and interacted and made decisions to change. I didn’t consciously set out to write a philosophical novel. It was more a case of being curious about the thoughts and feelings of people grappling with the question of how they should live – a question that I too am intrigued by! The particular freedom of reading and writing fiction is that one can be present in rooms where people are alone, and can peer into the minds of characters and see what they are truly thinking!

Having written across forms – the novel, short stories, novella – which do you feel is the most challenging, as an author?

The novel so far was the biggest challenge, mainly due to the many characters and stories to organise and arrange in a composition that would work as a whole.

What are you working on next?

I’ve been working with a series of Grimms tales and old folk tales to explore aspects of motherhood, which will hopefully lead to another novel. I’m also working on some new short fiction.

The Sunday Times Sri Lanka – January 2020

A villa, a fictional place and a socio-political commentary on Sri Lanka

By Adilah Ismail

In Amanthi Harris’ novel Beautiful Place, the beauty, kindness and joy of a place and its people coexist with violence, cruelty and sorrow. Published in September 2019, the novel is centred around the inhabitants, guests and bystanders at Villa Hibiscus, a house by the sea along Sri Lanka’s south coast.

Born in Sri Lanka, Amanthi grew up in Colombo. She currently lives in the UK and has written and published short stories and a novella. Amanthi also has a Fine Art practice using drawing, painting and 3D and has exhibited in the UK and Spain.

Amanthi Harris: Fond memories of growing up in Wellawatte. Pic by Maxi Kohan

In this email interview with the Sunday Times, the author discussed her memories while growing up in Sri Lanka, her creative practice, career and more.

- Could you share some of your experiences with Sri Lanka? What are childhood memories of Sri Lanka which have stuck over the years?

I grew up in Wellawatte, mostly in my grandparents’ house which was next-door, so close, that the two houses were joined by their kitchens! I have many wonderful memories of that time, mostly a sense of warmth and acceptance and being in nature despite living in the city. During school holidays every morning I would go over the Galle Road with my grandparents to Kinross Beach and my grandfather would jog and my grandmother and I would walk in the sea or draw in the sand with sticks. We all three liked to draw (my grandfather designed houses and my grandmother designed embroidery for a dressmaking business she ran) and we were always politely fighting over any spare paper lying around the house.

- Your website mentions that you’ve been a trainee solicitor, an editor of law books and bookseller, “writing and making art along the way”. Has your career path affected your creative practice? And if yes, how?

My career as a lawyer was short-lived, mainly as it was only when I was sitting in an office working on cases all day, that I realised I had trapped myself in a place where I could not think and dream and write– something I had vaguely imagined I would be free to do once I had left University. Finally, after much agonising,I left the law firm and worked as a bookseller in a lovely literary second-hand bookshop where my job was to sort the boxes of books that came in and to arrange them on the shelves- which was how I read my way from A to Z, discovering the wonders of Colette, Marguerite Duras, Hemingway, Kawabata, D. H. Lawrence, Katherine Mansfield, Jean Rhys, Virginia Woolf and many others. It was the education I had craved! I wasn’t very business-minded – sometimes I was paid in books – but what marvels I still have to return to!

The whole saga taught me not to be afraid, to believe in things turning out fine when you do what you love, and I’ve had no trouble leaving awful jobs since then, e.g. editing law books. It has also made me very committed to my creative practice and to own it fully. I am still amazed at how easy it is to work really hard at something one truly loves!

- How has getting published and being accessible to a wider audience over the years impacted you as a writer?

Beautiful Place has only been out in the world for a few months so it still feels too early to know, although good reviews in the press and having people say that they enjoyed it has been very satisfying – and surprising too, as I’m only now getting used to the book existing outside my head!

Prior to the novel being published, I had short stories in anthologies and broadcast on BBC Radio 4, and when these were received positively it was very reassuring and gave me the confidence to keep working on new pieces.

Winning the Gatehouse Press New Fictions Prize in 2016 with my novella Lantern Evening made a big impact, as the longer form had enabled me to try a new story structure, and to write about something I really wanted to explore but wasn’t sure if anyone else would be interested in (the ambivalence of new motherhood) so it felt risky and to some extent pointless entering the story into the competition. Winning it was shocking and incredible. It gave me the confidence to follow my instincts with the novel I was working on, which went on to be Beautiful Place.

The story is set in Sri Lanka and references locations in the country, but a lot of the action takes place in a villa close to a fictional beach, Nilwatte.

- Could you take us through the process of placemaking in Beautiful Place? Was there a reason you wanted this beach and place to be fictional?

Nilwatte Beach is a made-up beach on the South Coast, and being completely fictional, gave me the freedom to create the exact place that my story needed. The villa was central and I started there, but as the characters’ stories progressed the world of the novel grew outside the gates.

- There is a book referenced within the book and there’s a sense that the guidebook excerpts act as a narrative device to provide Sri Lankan history and socio-political context to readers. Were you perhaps conscious of your audience when writing the book?

I have always loved the idea of small specialist pamphlets about a place or topic – something very specific and contained. As Jarryd’s character developed, the guidebook seemed very much like something he would decide to write one day, so I started it as a separate project and then felt certain extracts might work in the novel. I could imagine the guidebook Jarryd would create so clearly: the type of paper, the font, the cover!

- The insider-outsider status of characters like Gerhardt and Jarryd and the locals’ ambivalence to these characters and resulting tensions are interesting. Could we discuss this a bit and how it came to be in the novel?

Both Gerhardt and Jarryd are idealists, full of eagerness for a life of beauty and freedom and passion and they are inspired to strive for it through their love of Sri Lanka. Their great privilege as insider-outsiders – and ones with wealth – is this power to desire and to have, and to be able to create the paradise they yearn for. But change is inevitable, and I was keen to explore how a paradise ends and also how it might be consciously dismantled and abandoned, and how one emerges from it to begin another life.

What’s next on the pipeline?

I am putting together a collection of stories and mulling over ideas for the next novel.

From Pasan Jayasinghe in THE HINDU (14/12/2019)

Sri Lanka’s beauty may be paradisical but the darkness of violence overhangs it. This book sketches the light with more ease than the shadows

Fiction set in Sri Lanka is often haunted by the paradox of the island’s obvious physical beauty and its equally present darkness. Amanthi Harris attempts to make sense of both in Beautiful Place.

Next to an idyllic beach in southern Sri Lanka, the young and bright Padma lives in a lush villa. Its owner, designer and Austrian expat Gerhardt, adopted Padma when she was young, from her abusive father, Sunny, who had tried to sell her to him. Gerhardt pays Sunny to keep him away from her. After a failed stint at university in Colombo, Padma returns to the villa to open it up as a guest house, and finds her life beginning to commingle with a slow stream of guests who are also searching for purpose.

Family trappings

Sri Lanka’s beauty is exotic and expansive in Beautiful Place; Harris paints sunsets and frangipani trees, beers by the beach and spicy fish curries, sunshowers and humid nights, in consistently rich detail. This, however, is easier than capturing the country’s darkness, especially placing it next to the beauty. Harris approaches the task in multiple ways. Outside her villa, Padma’s seaside tourist village swirls with drug dealers, brothels, corrupt politicians and watchful eyes, under the ever-present spectre of violence. There is a comic book element to these depictions, especially the violence, through Sunny’s criminal presence and the increasing threats to Jarryd, Gerhardt’s bohemian yogi friend, who has written a controversial book on Sri Lankan society. Escalating turns of the fist, knife and pistol sit a little too simplistically beside the lush setting, as if the complement to ‘beautiful place’ is always ‘ugly people’.

Fortunately, more nuance in the dichotomy can be found elsewhere, as Harris takes on growing societal ructions in contemporary Sri Lanka. There is growing class resentment, portrayed through the villagers’ envy of Padma’s inherited wealth, and their bitterness at being enmeshed in the pervasively corrupt and criminal tourist industry. The novel does not, however, press too hard on the happy service of the array of housekeepers, cooks and drivers attached to the main characters. This leaves their rarefied privilege intact, and doubles up perhaps to underline the fantastical quality of Padma’s unusual life.

Rising Sinhala Buddhist extremism is also hinted at, particularly through Jarryd’s encounters with elements provoked by his book. Extracts of it scattered through the novel do nevertheless border on being distractingly didactic – an unnecessary CliffsNotes to a place Harris is much better at describing.

More successful are Harris’ judicious takes on family as a source of darkness. Padma’s upbringing with the caring, sensitive Gerhardt has freed her from many conventional Sri Lankan family trappings. Yet her biological family — Sunny, her apparently subjugated and ailing mother Leela, and wayward, criminal brother Mukul — constantly intrude on her life, bringing with them bitterness, suspicion and violence.

Invisible lines

Elsewhere, Padma’s guests, who are all escaping their predetermined futures set by their families in one way or the other, capture the oppression created by family expectations. Harris renders the burdens of obligation, as applied to career, marriage and who you’re seen with and where, in claustrophobic detail.The novel endorses unconventional families and free choice as the key to happiness. While its characters are able to exercise this choice more freely than most, Harris commendably does not paint them as immune to the pressures created by any arrangement of love. Padma wonders how her life would have been without Gerhardt who, in turn, worries that his expectations for her have smothered her.

Harris’ approach to her characters is considerate and quietly affecting. This is particularly successful when the meandering between characters leads to the viewpoints of one being evaluated by another — the mental sizing up of each other by Padma and her guests is often filled with amusing, sparkling energy. At times, however, the characters’ constant examining and re-examining of their own motivations creates a languid repetition, which adds to the book feeling inflated.

Throughout Beautiful Place, the idea that Sri Lanka is a place of splendour so long as its deeper structures are not questioned rings true, and feels particularly apt in a tourist context. For the foreigner wanting to get away, indulging in the simpler pleasures and paying lip service to the locals is enough to retain the image of the place.

Things become more complicated only when the invisible, unspoken lines between country and guest, foreigner and local, wealth and need are probed a little too intently, as Padma and Gerhardt find out.

In the end, the novel does not come to any resolution between Sri Lanka’s beauty and darkness, for there really can be none. Suffering for good people and providence for the bad are constants, even in paradise.

For those lucky enough to be able to experience the beauty and avoid the violence, the fiction of the island can be maintained. Beautiful Place shows, however, that even for those that fortunate, the illusion collapses so very easily.

The writer is a researcher based in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

From Somak Ghoshal in MINT LOUNGE (06/12/2019) Ten years of tragedy in Sri Lanka

It has been 10 years since the civil war in Sri Lanka ended, though the long shadow of tragedy continues to haunt the island nation. On 3 December, the British Broadcast Corporation (BBC) reported that around 20,000 people, mostly Tamils, are still missing. The survivors continue to live in fear of reprisals, especially from the government of the new president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who was elected to office last month. Nicknamed “The Terminator” for his ruthless handling of separatism, he has already prorogued the parliament till January, while journalists who carried out investigations into his track record are being rounded up by the police.

The fractured history of Sri Lanka has been powerfully chronicled by several foreign journalists. Frances Harrison’s Still Counting The Dead (2013), Samanth Subramanian’s This Divided Island (2015) and Rohini Mohan’s The Seasons Of Trouble (2016) are essential reading to understand the costs of its long-drawn war. Yet history and reportage, while being potent documents of injustice, cannot always reach into the inner lives of their subjects—a domain often best accessed by fiction. In the last few weeks, three new books have appeared that aim to capture the human face of the Sri Lankan conflict through stories of love, loss and forbearance.

….

In Beautiful Place (Pan Macmillan, ₹599), Amanthi Harris captures the depredations of Sri Lankan society in more recent years, once again through the stories of individuals. At the centre of this nearly 500-page-long novel is Padma, adopted by an Austrian expatriate architect, Gerhardt, from her abusive and emotionally manipulative family when she was a little over nine years old.

As the story opens, Padma is running a guest house out of a beautiful villa designed and built by Gerhardt by the sea outside Colombo. Into this world of deceptive calm arrive a series of visitors, each on the run, either away from unsavoury pasts or on the lookout for safer futures. As their lives intersect, Padma and Gerhardt become embroiled in their trials and tragedies, as does the local community. Eventually, it is Rohan, a British-Sri Lankan man, who goes on to play a crucial role in Padma’s life, enabling her to escape the fetters of her upbringing and misplaced sense of obligation towards a family that has only ever wished her ill.

In spite of its girth and digressions into subplots, Beautiful Place is a breezy read. Through the lives of the people who visit Villa Hibiscus, the guest house, Harris creates a snapshot of a certain demographic in Sri Lanka: upper class, expatriates, English-educated, yet some of them also profoundly conservative and politically corrupt. The locals, poor fisherfolk, sex workers and pimps, resent the entitlement with which these city-bred visitors strut about but also cannot do without their munificence. The settlers, especially foreigners, have to tread a fine line, turning a blind eye to political misdeeds for the sake of peace and stability.

The story takes a sinister turn as one of the expats, a yoga teacher called Jarryd, is abducted and brutalized by goons for writing a tourists’ guide to Sri Lanka that doesn’t look away from the country’s nefarious political realities. Harris writes the ambivalent dynamics between the locals and the foreigners with sensitivity. Like many postcolonial nations, Sri Lanka, in her book, is a society in flux, determined to carve its unique identity and messily entangled with the liberal projects of the democratic West. While it is impossible to separate one from the other, their uneasy overlap is also the root of many pressing troubles that continue to haunt the subcontinent over 70 years after the end of colonial rule.

From GRAZIA INDIA (10/10/2019)

Amanthi Harris On Her New Book: Beautiful Place

by Barry Rodgers | October 10, 2019

This emotionally charged debut novel resonates like a deeply felt memory.

A quick scroll through Sri Lankanborn author Amanthi Harris’s bio on her website makes it apparent that she doesn’t take herself too seriously: “I’ve been a terrible trainee solicitor, a very bored editor of law books and a blissfully contented bookseller, writing and making art along the way”. But, her unflinching honesty around the subject of leaving and losing home in her debut novel, Beautiful Place, is anything but trivial. Centred on Villa Hibiscus, a guesthouse in the beautiful southern coast of Sri Lanka, the expansive and multi-layered novel traces the life of Padma, her stepfather, Gerhardt, and the lives of the many guests coming to stay, each seeking a better life and independence, free of oppression and misrepresentation. We caught up with Harris, and here’s what she had to say about the book.

GRAZIA: Why is Villa Hibiscus symbolically important in the novel?

AMANTHI HARRIS: The Villa Hibiscus is a place of safety, hope and beauty, where one can be inspired, live simply, and be part of a loving, supportive community. All of the characters in the novel are striving to build such a world, to find their way to happiness and a life of worth and purpose.

G: What makes Padma a relatable protagonist?

AH: Padma is young and full of promise and hope, brimming with an eagerness for experience that compels her to embrace the challenges of living a true life. She represents the youthful, fearless longing in everyone; her confusion, fears and insecurities are those faced by anyone seeking to define their path.

G: Describe the function of location (Sri Lanka) in the novel. How is it used as a larger metaphor for the connection between Padma and her stepfather, Gerhardt?

AH: I was born in Sri Lanka and grew up there as a child in a household of warmth, openness and intense creativity; an island of its own as political tensions simmered outside, presaging the turmoil of the war that was to come. In some ways, the villa was my attempt to recreate this remembered paradise and to explore it through Gerhardt’s momentous act of taking Padma into his life one lonely, dark night. So, Sri Lanka, in this instance, is perhaps a metaphor for childhood, that longed-for place of love, beauty and true belonging that must be held onto as well as left behind.

From Ben East in THE OBSERVER ( 17/11/2019) :

Beautiful Place

Amanthi Harris

Salt, £12.99, pp560

Sri Lankan-born Amanthi Harris won the Gatehouse Press new fictions prize for her novella Lantern Evening in 2016, but Beautiful Place is an altogether more ambitious work. Set around the Villa Hibiscus guest house on the southern coast of Sri Lanka, Beautiful Place features a global cast of characters who are all in some way searching for identity, family and a place to belong. It’s something of a quiet epic, a lengthy novel to relax into, but with a seismic event that forces everyone to reassess their loyalties and what a better life might mean. As the title suggests, Harris has a keen eye for a sense of place, and though the pace is slow, the mood and emotion are compelling.